EPISODE 3

GHOSTS OF JESSAMINE

A woman makes a horrifying discovery buried in her backyard. A Black preacher reckons with his grandfather's story of a lynching beside the statue.

THE EPISODE IN PICTURES

THE EPISODE IN VIDEO

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

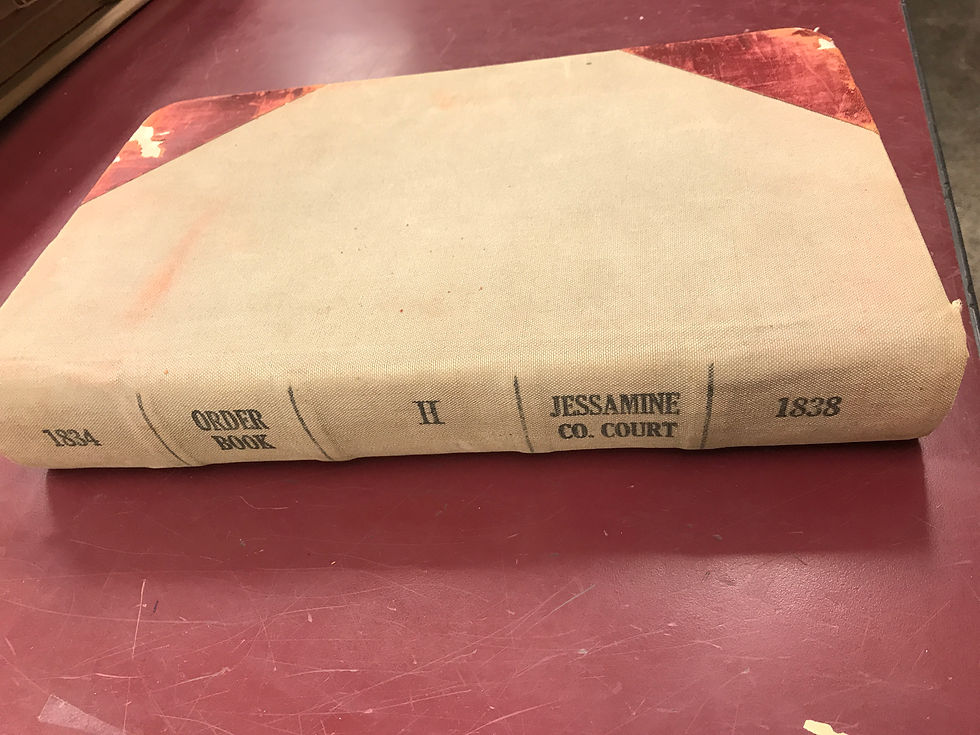

DAVID: The past is never dead. It’s not even past. I’m your host David Swartz. This is “Rebel on Main.” Episode Three: Ghosts of Jessamine. DAVID: One hundred years ago, Main Street was the place to be. Especially the block in front of the courthouse. Every Saturday morning folks came . . . for the shopping . . . and the people-watching. So many drove in from the countryside that it was nearly impossible to find a parking spot. If you managed to find a good one, manners dictated that you leave your vehicle unlocked so that other people could climb inside to rest. It wasn’t unusual to return with armfuls of bags . . . only to find complete strangers snoring away in your car. They say no one ever had anything stolen. It’s the kind of hospitality I fell in love with when we moved to Jessamine County, Kentucky, a decade ago. I can see why the tourism department released a promotional video called “Jessamine County: Home of Horses, History, and Hospitality.” The video features stunning aerial footage of the courthouse, the Civil War site of Camp Nelson, and the farm that produced Triple Crown winner American Pharoah. The landscape is so beautiful and welcoming with its stone fences and elegant horse farms. This video is a true story of Jessamine County. I know it because I’ve experienced it. I’ve been on lots of beautiful hikes here. People smile when you walk by. And they’ll do just about anything to help you out. But I’ve heard other true stories too. About slavery, segregation, even whispers of lynchings. In this episode I’ll take you with me on a kind of . . . violence tour of Jessamine County. We’ll dig through archives, encounter ghosts in a rural backyard, and listen to the stories of Black ministers in their churches. My goal is the same as that of civil rights activist James Baldwin: “to tell as much of the truth as one can bear, and then . . . a little more.” So here’s your warning: This episode may not be suitable for all listeners. PART ONE: GRAVES OF THE ENSLAVED DAVID: First stop on our tour: a graveyard. At least, I think it’s a graveyard. MAREN: You can see we think it looks like there’s an “H” carved in the top. And I feel like there’s a design, if you look under the “H,” it almost looks like four lines coming out. DAVID: This is Maren McGimsey. I first encounter Maren when she begins posting on social media about some possible graves of enslaved people on her property. Way out in the country toward Camp Nelson, near Jessamine Creek. MAREN: A few months after purchase, we were given a piece of paper that was about the history of this particular area. And in it, it stated that there was a cemetery for people who had been enslaved in the back part of our yard. And, you know, we kind of walked back there and looked. We saw what might be a small tombstone or something and then really just left it alone. DAVID: The slab of stone in question is tucked in between what we here in the Bluegrass call “trash trees”—scraggly things that live only 10-15 years. If this stone really is a grave marker, it’s a far cry from the elegant obelisks up at the landscaped Maple Grove Cemetery in downtown Nicholasville. MAREN: From what I understand, the animal barn was kind of where that house is. So you would have had animals knocking things over, so we’re lucky that we have that one. DAVID: And all around, there are other broken stones covered in moss. It looks like it could be the vestiges of a small cemetery. If that’s what it is, I’m standing amidst the remains of people whose stories were untold for 200 years. And remained untold. Until . . . MAREN: [laugh] This is the part where I’m going to sound like a crazy person. Over time, as we lived in the house, things began happening. DAVID: It was the spring of 2020. Maren started spending more time at home because of Covid. MAREN: I can a lot of my own things. DAVID: She’s talking about canning food, putting up tomato sauce and corn relish from vegetables she grows in her garden. MAREN: And I was canning one day, and I heard a noise in my walk-in pantry. And a jar that had been sitting far back on the shelf had somehow been lifted off the pantry and rolled across the floor. DAVID: That’s not all. MAREN: We had times when the dogs were fed when nobody was home. . . . And I would hear whispering in certain parts of the house. DAVID: It was around this time when Breonna Taylor and George Floyd were killed. MAREN: This year has been very, I think, restive on a lot of levels. And I think it is restive on a spiritual level. DAVID: As protests began at the Jessamine County courthouse, the ghostly activity at Maren’s house spiked. MAREN: A mirror that was mounted on the wall was thrown off the wall. . . . And that’s when I decided that maybe someone was trying to get my attention. DAVID: She developed a theory. MAREN: I don’t know how it works in the afterlife, but I wonder if . . . people who’ve been marginalized and haven’t had their names recorded in the record . . . maybe sometimes they find a way to communicate and say, “We were people. We had names. We lived. And we want that acknowledged.” DAVID: But Maren couldn’t acknowledge them. She didn’t even know their names. MAREN: So I, kind of, am really intense. I love to research. I used to be a paralegal. So once I decided to go for it, you know, I just started digging in. I’ve been crawling around in the county clerk’s records, pulling down these records that are, you know, 200 years old to look through and kind of see. DAVID: But those early records, Maren discovered, sometimes aren’t very helpful. MAREN: The biggest problem is that slavery as an institution worked on erasure. DAVID: You can see it in the Vital Statistics Records for the state of Kentucky. MAREN: Even though there’s a space for the name of the mother of a child that’s born enslaved, they wouldn’t put it there. Very rarely you might see a first name, but they wouldn’t put it. And they wouldn’t put a father’s name. They put the name of the owner. DAVID: Federal census records are even worse. MAREN: In the 1820 census and some of the older ones . . . they just list a hash mark. This many Black people between this age—and this many white. DAVID: The record-keeping got a lot better in 1850 and 1860. Slave schedules were added to the census. Still no names, but they did include age and gender and color. But it wasn’t until Maren dug into the court documents that she made her first big discovery. MAREN: My first name was Jane. I found a little girl named Jane. . . . She was the six-year-old girl that had been listed on the slave schedule. And I found her birth record. And so that was super, like, super exciting. It was just amazing. Since then . . . I think I’m up to nine names. DAVID: Maren also learned more about Jane’s enslaver. MAREN: The original property owner, William Phillips, moved here from Virginia. DAVID: He came . . . in the year 1800 . . . with his wife Elizabeth. MAREN: And the reason that they bought this land was because he loved to fox hunt. And this was very rich, we still have tons of foxes. DAVID: The foxes, though, didn’t make up for an unhappy marriage. MAREN: He kind of like moved here and then ditched her with the kids and kind of ran around. And then he died in 1815. DAVID: As a woman, Elizabeth wasn’t allowed to manage any of the money or property William left behind. MAREN: So anytime she needed a payout, there’s a court record of the payouts. . . . And those are all in the clerk’s records. DAVID: Most of the records have to do with payment for clothes, school tuition, and so forth. . . . But then Maren found the final estate settlement. MAREN: So that’s where I was able to find the first notations of people that they had here on the property that were enslaved. . . . They had to determine what to do with the slaves. . . . DAVID: “They” is Elizabeth’s children, siblings who stood to inherit the property. MAREN: And the siblings all drew straws, and each one got to choose a slave. And then they had to pay the mother. So for instance . . . Harrison draws a slave named Mary and has to pay $300. . . . So Buford, one brother, draws Sam and has to pay 33 1/3 percent for his share. DAVID: Maren finds this horrifying. MAREN: You’re like, these are humans. These are human people. They’re literally drawing straws and paying each other. . . . It’s just stunning, absolutely stunning. DAVID: And this is just one small family in Jessamine County, which was just one of about 100 counties in Kentucky, which was just one of fifteen slaveholding states. At the start of the Civil War, Kentucky enslaved a quarter of a million human beings. The country as a whole enslaved four million people. MAREN: One of the biggest problems we have right now is that people don’t understand the scope and structure of slavery in the United States. I think that they think that it was kind of this informal thing, that people had some slaves and oh, you know, they took care of them, and they fed them. They were this high-valued piece of property, so obviously they took care of them. Like that’s the narrative you hear. And it’s when you look at the actual primary sources that you begin to see that this is something that is codified in law. And it permeates every single aspect of the legal system. DAVID: In fact, before the Civil War began in 1861, these legal structures made emancipation very difficult. It was hard even for the few enslavers . . . who might want to free their human property . . . to do so. MAREN: There are manumission records, not a lot, but here and there. And they actually had to post a bond for people who were given their freedom . . . a very large bond, saying that these people will not become a charge. Which is, again, that systematic structure to say that even if you do want to free this person, we’re gonna make it really punitive. DAVID: This is a really important point. Legal codes are disincentivizing emancipation. MAREN: [30:50] Oh, you might want to do that, but it’s gonna cost you. You know, so how many people are actually going to do it? DAVID: This reminds Maren of one of the most vilified regimes in world history. MAREN: This is just like the documents you see after World War Two, when we’re looking at the function and structure of the Nazi government. . . . I always say it’s like the banality of evil. . . . It’s bureaucracy. It’s paperwork. It’s forms. It’s saying on every single one of these, we’re going to make sure that you’re nameless and faceless. . . . It is profoundly sad. And then it’s very troubling. . . . . Like, we should all be very troubled. DAVID: The more she looks at the slave schedules, the more troubled Maren gets. MAREN: They’re very specific about saying whether someone is black or mulatto. Black is obviously two black parents. . . . Mulatto means that there was someone white involved. And in looking at Jane, she’s listed as mulatto. . . . It becomes very clear that this was likely the child of rape from the person that owned Jane’s mother. DAVID: Jane wasn’t the only one in the lists. As the Civil War approached, there were an average of eight to twelve women and children on the Phillips’s property at any one time. All the women were recorded as Black. Nearly all the children . . . mulatto. MAREN: What’s the easiest and cheapest way to increase your most profitable asset? You already have the tools, right? You’re a male. . . . He already had the tools to go and increase. . . . There’s no law that says, “You can’t rape these women,” is there? There’s no way for them to fight back. And as you go through the records, it’s like, oh, you know, more and more of these children are being listed as mulatto. Why is that? And, you know, that’s another thing we don’t want to confront. DAVID: Maren is doing her best to confront it. On social media she has begun posting about her research. After her first visit to the county clerk’s office she writes, “I am truly in shock. I found the first name. There was a little girl born on this land and her name was JANE. . . . Say her name. Jane. She was here, she was a little girl who ran the same fields and woods as my own children. Is she buried here? I don’t know. But I do know Jane existed, and I know her name, and I didn’t know that before.” A day later . . . Maren writes, “The next time someone tells you that there was mass rape of Black women by slaveowners and you are disinclined to believe them, please come and see me. We can walk through the census records together. But it’s easier if you just believe them.” Maren’s posts are getting a lot of attention. “Oh my God,” reads one typical response. To many of her followers, it’s a revelation. But not to everyone. Not to those already haunted by these violent stories. Casondra Radford, daughter of Pastor Moses Radford, replies to Maren’s post. CASONDRA: “My dad’s grandfather was the product of ‘Master Humphries’ and a slave.” “This was so very common.” DAVID: The next time I get together with Pastor Moses, he tells me more. We’re sitting in his church, which dates back to 1846. That’s fifteen years before the Civil War even began. MOSES: My daddy’s grandfather was the child of the white master. My grandpap, child of the white master. DAVID: He had recently explained this to an interracial group of local clergy. MOSES: And I asked the group, “Do y’all think that she, his mother, willingly lay down to be impregnated by the white master?” Everybody sat there and looked at me for a second or two. Then somebody said no. I said okay. That’s history. I said how many white masters took our great-grandmothers by force? DAVID: He then took the opportunity to criticize the Confederate statue in Nicholasville’s town center. MOSES: I said, “Y’all want some history on the yard? Let’s make a statue of a white master raping a black woman. Put that on courthouse yard.” I said, “That’s history. That’s real history.” I say, “Would y’all be offended if we did that?” Yeah, we would be. I said, “Why? It’s history. . . . Just like you all would be offended by that, that Confederate statue is very offensive to us.” And they said, “Yep, We see it. We see what you’re saying.” [chuckle] DAVID: Pastor Moses isn’t done yet. MOSES: If they really want history, tell a real story. How the white man come here, took the red man’s land. And turned around and brought the Black man to work it. They got all the cash and all the credit, worked our ancestors worse than . . . dogs and pigs and cattle. Probably treated snakes better. They really want the history? They need to go and rewrite a whole lot of stuff. You know, they don’t want the history. They want their history. Twisted history. DAVID: As all this plays out locally in the summer of 2020, I read an article in the New York Times. One of the most gripping articles I’ve read in my life. It’s by poet Caroline [line] Williams and is entitled “You Want a Confederate Monument? My Body Is a Confederate Monument.” Here’s Casondra Radford reading a few of Williams’s lines: CASONDRA: “I have rape-colored skin. My light-brown-blackness is a living testament to the rules, the practices, the causes of the Old South. I’ve got rebel-gray blue blood coursing my veins.” DAVID: If monuments make tangible the truth of the past, then she and Casondra and Pastor Moses and just about every other Black person in Jessamine County are truer Confederate monuments than the one standing on the courthouse lawn. No wonder they want the statue removed. That soldier had fought to preserve the institution that gave them rape-colored skin. To them, he is nothing to celebrate. And yet, the statue . . . has a celebratory cast. He stands high in the air, gazing triumphantly across Main Street. And the plaque on the base says he fought for quote “no greater cause.” For Maren, this is cause for lament. MAREN: I don’t think we’ll ever get anywhere until we have some kind of national time . . . of repentance and mourning for the actual way in which our country was founded. Yes, we had these really fabulous words that were written. They were fantastic, you know, beautiful. But we also implemented slavery when we had a choice not to. And the revisionist history that says, “Oh, they didn’t know any better.” It’s just not true. They did know better. John Adams was saying, “This is wrong.” DAVID: She’s referring to the second president of the United States, who never personally enslaved people and, in fact, loudly denounced the practice. MAREN: But then he’s also kind of complicit because he went along with it, right? DAVID: She’s right. John Adams supported the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, which allowed slavery to continue. MAREN: We have to look at that and say how complicit everyone was. And I just don’t think that we’ve really done that. DAVIDBut Maren is trying. She’s naming names. The Founding Fathers for writing slavery into the Constitution. The Phillips family for enslaving Jane’s mother, whose name Maren still doesn’t know. No wonder she’s seeing and hearing ghosts. The graves in her backyard demand a reckoning. PART TWO: BURIED STORIES DAVID: The second stop on my tour is notable for the violence I don’t find. At the weekly gathering of the Jessamine County Historical Society, I discover an old VCR tape. It’s a recording of an outdoor drama staged in 1987, the eve of the county’s bicentennial. After rooting around shelves and filing cabinets, I finally find the right cords and equipment to play the tape. Half a dozen other historical society members settle in to watch with me. 1987 DRAMA: Enjoy yourselves and relive the old times during “Jessamine.” . . . DAVID: It’s a charming—and impressive—production. There’s period costuming, elaborate choreography, pyrotechnics, real live horses, and a homegrown cast of more than 250 actors. 1987 DRAMA: Jessamine County 1774 was not all music and dancing. DAVID: At the beginning it’s narrated by the character of legendary woodsman Daniel Boone. 1987 DRAMA: Becky, remember that night back in 1769 when John Finley came by our cabin there in the woods of North Carolina? Remember how we welcomed him to the fireside, and he told us over and over again about his journeys to . . . the place where he saw the buffalo that were like herds of cattle, and deer would lick out of his hand. DAVID: Finley and other Revolutionary War veterans settle the land, fight with Indians, and set up a local government. Everyone looks good. The pioneers, who import southern gentility, are hard-working and brave. The Indians are noble and fierce. And the only Black man who makes an appearance . . . is selfless. 1987 DRAMA: We had this fine Black man, Cupid Walker, who was the custodian of our church. He would carry in the wood, build our fires, clean and fill our lamps, keep the church spotlessly clean, and look after all our needs. Why was he called Cupid? I really don’t know. Perhaps he because he just went about making things pleasant for everyone. DAVID: “Pleasant” is a peculiar way to describe the service Cupid performed in the county, especially during the cholera epidemic of 1850. 1987 DRAMA: Quietly moving about through town, and when he’d come to a home where a body had been placed outside the door, he would gently pick it up, carry it to the cemetery, and bury it. And in his way, he somehow marked each grave. DAVID: That’s it. Black history as faithful service to the white citizenry. There’s no mention of how exceptional Cupid Walker was . . . in being a free Black man. In 1800 only 1 percent of the Black population was free. And a full 40 percent of Jessamine County’s population was enslaved. As we sit there watching the drama, we don’t hear the word slavery a single time. Jessamine County appears to be a racial utopia. Even as the South secedes from the United States. 1987 DRAMA: It was on an April Sunday in 1861 when the War between the States began. DAVID: State against state. Brother against brother. Father against son. And throughout . . . all sides are portrayed as courageous and righteous. That is, until thirty years after the war, when Confederate memory overtakes Union memory. 1987 DRAMA: The largest and most imposing public monument in Jessamine County is in the courthouse yard. That tall soldier with musket is in memory of the Confederate dead buried in Maple Grove Cemetery. . . . Special trains were run into Nicholasville, and Jessamine County historian Col. Bennett Young brought a delegation from Louisville. DAVID: On screen a white cloth is pulled from a cardboard cutout of the statue. The audience breaks into applause. And the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” swells. This abolitionist song, ironically enough, baptizes the Confederate monument. And as the drama marches into the twentieth century, Union memory is never mentioned. Emancipation as a war aim is never mentioned. Black people voting for the first time after the war is never mentioned. In 1896—and still in 1987—the only memory of the Civil War on the courthouse lawn . . . is Confederate. CHOIR: Glory, glory, hallelujah. His truth is marching on. Amen. [clapping] DAVID: The production primarily drew its inspiration from a book entitled A History of Jessamine County by Bennett Young. Yes, that Bennett Young—the architect of the Confederate statue and thirty years earlier, the leader of that crazy raid on St. Albans, Vermont, during the Civil War. Written just two years after the statue was erected, Young’s book minimizes Black suffering. In the historical society I found half a dozen other histories of the county. And they all suffer from the same troubling amnesia. They rarely, if ever, mention the violence of slavery. As I page through these histories and watch the drama, I’m struck at what a fundamentally different story they represent than what Maren is uncovering in her backyard. And what I, as a historian, know slavery in the South was like. Wanting to take the full measure of Bennett Young’s complicity in slavery, I invite Maren on my next “violence tour” stop. She agrees to meet me at the courthouse, which is just across Main Street from the historical society. DAVID: All right, it’s a cloudy May morning, and . . . we’re about ready to go into the county clerk's office. And my plan . . . is to look for old records having to do with what I’m starting to call “plantation row.” DAVID: That’s a row of half a dozen plantations on Wilmore Road, a major road I drive on all the time. One of those plantations was Robert Young’s. He’s the father of Bennett. MAREN: Ok, so he’s the one who put up the statue? DAVID: Exactly. . . . And if we poke our head around the corner here, we can see the statue that went up in 1896. And Bennett gave the dedicatory address right there. So Maren here has been to the clerk’s office before and is going to show me the ropes. MAREN: Yeah, how to dig in the records. DAVID: Well, let’s go on in and see what we find. DAVID: Incredibly, we just walked in. Unlike most archives I visit, no one checked our identification or made us put on white cloth gloves. MAREN: I can’t believe they just let you touch this. It blows my mind. DAVID: And instead of historians, there were lawyers in suits doing deed and contract work. It didn’t feel like we should be there. But then I saw the old stuff. It was a historian’s dream. There were giant leather-bound books stacked high on the wall, so high that you have to climb ladders to reach them. There were deed books, will books, court records. The most exotic—and jarring—were the marriage books . . . with “White” and “Colored” still stamped on them. MAREN: Let’s go oldest record first. So we’ve got this record here. DAVID: Those don’t look right, do they? DAVID: They don’t match Bennett’s mother’s name of Josephine. Before long, we’ve opened five huge books—all spread out in front of us—looking for the right guy. MAREN: He’s kind of slippery. So what we’re trying to do is generally just get nailed down the details of, you know, address, first and last name, court things that were going on. DAVID: The writing gets . . . pretty sloppy. MAREN: As you saw with the marriage records, lamb was written as land. Young was written as gung. DAVID: It’s kind of unbelievable. This was one of the wealthiest men in the county, and we can’t locate him. MAREN: We’ll find him. I promise you. I can’t stand when there’s a thread hanging from something, so let’s see . . . DAVID: There we go. MAREN: We have finally found some records on Robert Young. And this is from 1830. So, likely who you’re looking for. DAVID: Turns out that he was in trouble. MAREN: Robert Young did not give their list of taxable property for the last year. . . . And so then let’s look at the next one, page 58. DAVID: Robert Young. MAREN: There he is. Ok. Now they’ve issued a summons against him. DAVID: It gets more intense. MAREN: They’re sending the sheriff out to get him! So now we’re going to go to page 208. Isn’t it fun? And here he is again. So he did show up in court “in obedience.” [laughter] . . . See, so that means he’s probably going to have to show it. DAVID: That takes us to the property books, which takes us to the will books, and so on. We find a lot of the disturbing material we expected. And it’s disturbing in part because of how routine and commonplace it was. Enslaved property listed alongside household items and farm implements. Enslaved families broken up when the Young family sold off property. But Maren and I also find evidence that really surprises us. MAREN: “So on the motion of Robert Young, who acknowledged in open court at the July term 1846, a deed of emancipation . . .” DAVID: So Bennett Young’s father emancipated someone! MAREN: “ . . . to his slave Philip, alias Philip Broadus, ordered that a certificate of freedom be now granted to said Philip Broadus, describing him to be about 49 years old of age, five-feet six-inches high of dark copper complexion with a scar on his left hand on the leader of the thumb and of erect form and statute.” DAVID: It’s a piece of evidence that fits what Confederate defender Sam Flora told me in the last episode. Something I found hard to believe: that the Youngs were racial humanitarians. That after the war . . . Bennett founded a colored orphan’s home. That Bennett acted as a defense [di-FENCE] attorney for a Black man who killed a white man trying to lynch him. And now we’re learning that Bennett’s father had emancipated a man named Philip. More than 150 years later, we’re left to wonder why. Were Bennett and Philip childhood playmates who cavorted together in Jessamine Creek? Were they half-brothers? With only sparse legal documents to go on, it’s hard to know. But on the face of it, it’s impressive. You don’t see many emancipation papers in the Jessamine County clerk’s office. As Maren and I piece together the Young story, I begin to see how the truth of racial violence got buried. Confederate apologists used partial evidence to build an incomplete interpretation of local history . . . an interpretation still told by the Confederate statue, the county’s history books, and the outdoor drama. And it’s not just Jessamine County. Similar formulas were employed throughout the American South following the Civil War. It’s a narrative . . . called the Lost Cause. In fact, just a few weeks earlier I had given a lecture on the Lost Cause to my students at Asbury University. I told them it consisted of four tenets. First, the Lost Cause lionized Confederate courage. The rebels were really brave. Second, it claimed direct lineage to the American Revolution, saying that the South’s secession in 1861 was a continuation of the patriotic revolt of 1776. Third, it cast the North as an industrial juggernaut that crushed the Confederacy’s farming paradise. And fourth, the Lost Cause maintained that slavery . . . was a good practice. [pause] This last one fit the property history Maren was given when she bought her place. The enslaved people, it says, were quote “treated well” and didn’t want to leave after the war. Maren’s own words, however, jar me back to the county court records. MAREN: “Whereupon said Young being so required executed a bond with Thomas Broadus his security in the penalty of $150 conditioned that said Negro man Philip shall not become chargeable to any county in this commonwealth.” DAVID: Let me translate. Robert not only gave up his property, but he had to pay money into a state fund in case Philip became indigent and had to rely on the state for care. Giving Philip his freedom papers was a costly act. MAREN: This is the catch-22 they have going through all these laws. Oh sure, you can free your slave. You’re going to have to pay $150. DAVID: In essence, this is discouraging the emancipation of slaves. MAREN: Yeah. Yeah. Because say you’re someone who doesn’t have a lot of money. You don’t want this slave you inherit. Like, you don’t ask for it, but you inherit a slave. So you want to free this slave? . . . Well, then you have to come up with $150 to do that. DAVID: And $150 back then was worth the equivalent of 55-hundred dollars today. MAREN: It’s a lot of money. DAVID: Kudos to the Youngs for spending that money. But this one family’s records also demonstrate how legally, economically, and socially committed Kentucky was to slavery. An institution, by the way, that made Robert Young a very rich man. When he died on Thanksgiving Day 1889 at eighty-six years old, he was said to be the wealthiest man in the county. He may have emancipated Philip, but he didn’t emancipate dozens of others. And to my knowledge, neither he nor his son Bennett renounced slavery, even after the war. To learn more about how slavery, racism, and the Lost Cause were linked . . . I sit down with Carolyn Dupont, professor of history at Eastern Kentucky University. People like the Youngs, she tells me, were true believers. DUPONT: The Confederacy was right in standing up for itself and standing up for the kind of civilization that they had created. But essentially, that the defeat was caused by disobedience to God. DAVID: They believed that their cause was right, even if it was lost. God was not punishing them for practicing slavery. DUPONT: I think maybe this is a good place to underscore how infused with religion the Confederacy was. And to just remind folks that the Confederacy was defended by preachers of the Baptist faith, of the Methodist faith, of the Presbyterian faith. And these preachers talked about slavery as a God-ordained system—and as a positive good for everyone involved. DAVID: So instead of repenting for slavery after the war, these former enslavers and their kind doubled down on racial hierarchy. And they invented the Lost Cause. Here’s the story they spun: DUPONT: Our ancestors, our fathers, and uncles and brothers did not die for an ignoble cause. They fought and died for something that was glorious. DAVID: Yeah, how do you see that glorious cause reflected in our Confederate statue here in Jessamine County? DUPONT: In our statue. Well, quite explicitly, because there’s an inscription at the base of that statue. . . . I think that this is an important thing to think about when we think about: Is it just history? No, it’s a specific interpretation, because the inscription at the base of that statue says, and you will provide the quote, at some point . . . DAVID: Yep—I can do that. Here’s the inscription on the west face of the statue: “Nor braver bled for brighter land. Nor brighter land had a cause so grand.” DUPONT: Going along with the reinvention of this cause as noble is a sort of collapsing, or a forgetting—I think that’s the best word—a forgetting of the fact that the war was always a war to preserve slavery. DAVID: Forgetting . . . The Confederate statue . . . itself a mostly-forgotten second-hand Yankee monument . . . is a massive exercise in forgetting just how terrible slavery was. In his dedication speech, Bennett Young fondly recalled a mythical civilization in which faithful slaves, virtuous women, and chivalrous patriarchs presided over a righteous South. Young was unrepentant. Consider this line: “There are many instances in history where the cause of the just is defeated . . . and where wrong has prevailed.” DUPONT: David, I’ve not stood there and gawked at it as much as you have. But the figure . . . is assertive, maybe even a bit aggressive. You know, he’s a soldier. He’s got intent. He’s forward moving. He’s not cowed. He’s not defeated. And so . . . we also just need to think about what a statue in a public place means. This is a place where we want to elevate our highest values, and literally the soldier is elevated. . . . And so to say that it’s not an interpretation, to say that it’s just the facts. It’s just the facts of history. I don’t think that . . . view can be supported. DAVID: And as the defense of slavery becomes less defensible, people reinterpret the interpretation. DUPONT: They reinvent the causes of the war as being about taxes or being about states’ rights. DAVID: Remarkably, the Lost Cause won the narrative war even in parts of the Yankee North. My mother recently told me that when she was growing up in Flint, Michigan, in the 1960s, she was taught that the Civil War was about states’ rights, not slavery. So this mythology . . . this MIS-remembering . . . is not just a Southern problem. . . . It has been a national problem. So far, this “violence tour” of Jessamine County’s slaveholding past has taken us to a rural backyard, the historical society, and across the street to the courthouse. Next I’m headed to the local library to read old copies of the local newspaper. But first there’s one last thing to see at the historical society: a video of the 1995 rededication of the Confederate statue. The video opens with two guys in true nineties’ garb—white t-shirts tucked into blue jeans. They’re standing on the statue’s base and draping a white veil over its head before the ceremony begins. The statue was in bad shape the last time a crowd had gathered in front of it. Originally a dark golden bronze, the soldier had aged. A thin film of copper oxide had turned him green and brown. Part of his bayonet had broken off too. As I look at the hooded statue on the television screen, it strikes me that the city fathers could have just let it fade and crumble like the Lost Cause it represents. Instead, they chose to restore it. The county hauled it to Louisville, where technicians scrubbed the mold and repaired the bayonet. Back home again in Jessamine County, the gleaming ninety-nine-year-old Confederate statue was again unveiled. This time the ceremony included the Stars and Stripes . . . and the song “America.” But to me it seemed that the crowd, many of whom were dressed in butternut uniforms and plantation dresses, really came alive for the Confederate battle flag . . . .” and the songs “Dixie” and “My Old Kentucky Home.” And, of course, the statue. Before my eyes, this Lost Cause statue . . . filled with so much forgetting . . . was being passed down to yet another generation. No wonder the statue still seems like good history to so many. PART THREE: TOM BROWN’S LYNCHING DAVID: The fourth stop on the tour finds me hunting through issues of the Jessamine Journal. DAVID: I’m at the Jessamine County Public Library working a microfilm machine. Ok, just opened the 1902 reel . . . DAVID: It didn’t take long to find evidence of the brutality that pervaded the South after emancipation. Historians call this era Reconstruction. It’s when the United States grappled with how to reintegrate the Confederate states . . . how to reconstruct the Union. It was hard work. DUPONT: When the surrender was signed at Appomattox, the South did not quit fighting. They did not quit fighting to subordinate African Americans. And so, you know, Reconstruction is this period of horrible violence against Black Americans, all aimed at depriving them of political rights. DAVID: In Jessamine County . . . the prejudice and violence continued well past Reconstruction. The first surviving issues of the Jessamine Journal appear in 1887. And they’re awful. Article after article uses the derogatory term Sambo to refer to Black people. It suggested that they were slaves to their bodily instincts. That they refused to look after their families and only ate, drank, slept, and fornicated. There are a few exceptions in the newspaper. Occasionally, Black people are called “faithful negroes” or “nurturing mammies.” These Black folk are lauded for having resubmitted to the expectations of their former enslavers. Those who had not fallen into line are labeled with the n-word or something similar. DAVID: Ok, here’s an article from 1889 entitled “Hell in Herveytown.” DAVID: Herveytown was the Black section of Nicholasville, just one block east of the courthouse. It’s where, according to this article, unfaithful negroes insulted white ladies. They forged checks, shot neighbors, molested their children, and desecrated the Sabbath by shooting craps. It’s one thing to hear historians describe the period after the Civil War as racist. It’s something more to read the actual words. And it wasn’t just words, says Professor Dupont, it’s how society itself was structured. DUPONT: They implement a series of laws that relegate African Americans to low status, put them in separate and inferior schools, when they offer schooling at all. forced them to work in these labor contracts that are very exploitative. DAVID: Like much of the American South, Jessamine County officials segregated neighborhoods, ballparks, churches, restaurants, cemeteries, even swimming holes. Signs all over town stated, “For White People Only.” There were unwritten rules too. Black persons had to step aside—and remove their caps—when encountering whites on the sidewalk. Black men had to avert their eyes when passing white women. Black people were not allowed to try on clothing in stores. They had to yield to white motorists at all intersections. All of these everyday insults and condescensions were maintained with threats of violence. DAVID: This headline on February 7, 1902, looks like it comes out of deepest Mississippi, but it’s here in the Jessamine Journal. It reads, “Quick Work: Tom Brown, Colored, Assaults a Young Lady and Is Hung to a Tree in the Court House Yard.” DAVID: The article explains that bloodhounds tracked down the Black teenager out in the countryside. Police then took Tom Brown to be identified by the young white woman who had accused him of rape. DAVID: I’m standing by the old jail in downtown Nicholasville. Tom Brown never made it inside. Right here on the sidewalk is where the mob violently seized him from the police. They dragged and pushed and carried him two blocks down Main Street until reaching the courthouse lawn. By then, the newspaper said, Brown was “more dead than alive.” At high noon on that Monday, a telephone lineman, holding rope in his hand, ascended a sycamore tree. On the ground the other end of the rope was fashioned into a noose and placed around Brown’s neck. Dozens of white hands then grasped the rope to swing the Black man up into the air. By 1 p.m. . . . Tom Brown was dead. DAVID: Back at the library, I read how it ends. DAVID: “After hanging to a tree for an hour, Brown’s body was cut down by Coroner Fain and taken in charge by Undertaker F. P. Taylor . . . Everything being conducted in an orderly manner.” DAVID: This narrative, says Professor Dupont, fits a larger pattern of lynchings. DUPONT: Many people think, you know, that it’s a frenzied mob foaming at the mouth, and . . . something overtakes them, and they go crazy. It’s actually not. It’s calculated. It’s rehearsed. It’s planned. It’s performed. There’s a ritual to it. DAVID: But the ritual didn’t include a courtroom trial. It’s impossible to know whether Brown was guilty. At the turn of the twentieth century, there were documented cases of Black men assaulting white women. There were many more cases, however, of white women, caught having consensual sex with a Black man—and then accusing him of rape to protect their own reputations. Whatever the case, the swift lynching of Tom Brown met no civilized standard of justice. There was no judge. There was no jury. Instead, the hanging was a warning. The Jessamine Journal declared, “May this serve as an object lesson to all who harbor these fiendish [feen-duhsh] thoughts in their minds, that our daughters, wives, sisters and mothers may have protection from such red-handed scoundrels.” It’s important to note that white men in Jessamine County did not serve as object lessons when they were in similar situations. They were given defense attorneys. DUPONT: Well, lynching is extralegal. . . . The message to whites is: We can do this with impunity, and we can dominate Black Americans, and we can control them. DAVID: The statue on Main Street, says Professor Dupont, reinforced this message. DUPONT: You know, it’s not just the one lynching in Jessamine County that was done next to a Confederate statue. If you look at these lynchings all over the South, a very large number of them are done in places where the Confederacy is memorialized: town squares all over the South. DAVID: She also points out that monuments go up in these town squares when lynchings ramp up. The timing is important. DUPONT: And so they’re absolutely connected, because both of them are saying to Black people, “We’re the boss. And danger awaits you if you don’t comply with the system and stay in your place.” DAVID: This combination of white supremacy, Lost Cause mythology, and lynching had a profound psychological effect on African Americans. I got a breathtaking glimpse of the anguish from a document in the archives. It comes from a college student named T. Thomas Fortune Fletcher. He was born in Jessamine County in 1906, just four years after Tom Brown’s lynching. And he was named after the renowned Black newspaper editor and antilynching activist T. Thomas Fortune. Fletcher’s father was a local teacher who protested the segregation of Kentucky railroad cars. And his grandfather had been enslaved before gaining freedom at Camp Nelson. When Fletcher went off to Fisk College in Nashville, he wrote a series of poems . . . heartbreaking poems. The first, entitled “Night,” goes like this: FAIN: “Night in the South / Is a black mother / Mourning for murdered sons / And ravished daughters.” DAVID: The second is entitled “White God.” FAIN: “God is white / Why should I pray? / If I called Him / He’d turn away.” DAVID: My next stop takes me down to Camp Nelson, where the generational trauma of slavery and lynching still reverberates. Robert Gates, pastor of the Baptist church there, tells me he has never entered the front door of the courthouse. That’s because he too connects the lynching and the statue. GATES: I don’t never go to the front. . . . I’m gonna tell you something. I’m sixty years old and probably no more than six months ago was the first time that I actually looked at that statue. My whole life, I have not. DAVID: The reason has to do with his grandfather, whose living memory dates back to the 1890s. He lived in Jessamine County when the Confederate statue went up. He was still there when Tom Brown was lynched. And then he passed on those memories to his son, Gates’s father. GATES: I always remember my dad, when we come to the courthouse, we never did go out the front. Never did. . . . Now in looking back and seeing what was going on, there was a reason why we didn’t go out the front. My dad didn’t want to see that. He didn’t want his children to see that. DAVID: And so Rev. Gates never did. . . . Not until six months ago. GATES: I said . . . I want to see. I’ve heard about it, but I want to be a witness to see what it actually is. . . . In my whole life, that was the first time I looked at that durned thing. DAVID: What did you see? GATES: I saw the hat. I saw the buckle. But what I saw was what Thomas Brown saw. That’s what came to my mind. What he had to see when they strung him up for something that maybe he didn’t do. . . . And I can just imagine that tree being out front, that sycamore tree that they cut down years ago. And for him to be hung on it, to see that monument, knowing why that monument was put there. And for that to be seen as a last thing, plus all that hatred of those people lynching him, and him being 19, a young boy. . . . And then I can say, I understand. Because I know. I’ve been lied on by some folks. And they’re not my color. So when I look at that, and I see what he saw. I saw the hatred, the evil, that people smile in your face, and they’ve got a hidden agenda. And that’s the reason why they do that stuff. . . . And then they want to keep that thing still up there for us to see it. How foolish! DAVID: What bothers Rev. Gates most of all is the statue’s location at the courthouse—the seat of justice in Jessamine County. GATES: They put it right in front. Not only for the white people to see, but for the black people—No, don't cross this line. DAVID: Remember, Herveytown—the Black section—is right across the street. GATES: . . . as a deterrent. Because that’s some of the things they do. . . . It was not set there by mistake. . . . Look at the courthouse, all those areas that they could have put it. . . . right on the edge, right on the corner. . . . You got just as much area on the right side. Or on the backside. . . . No, we want this right out in the front. And then the day that they placed it for all the people to come—it was like a picnic. DAVID: To Rev. Gates, picnics are ominous things. GATES: Oral tradition says that picnic was pick a nigga. . . . See, when there was a hanging, they have a picnic. Pick a nigga. You don’t hear me say picnic, because I know the history of it. DAVID: The history . . . is relentless. Slavery followed by Jim Crow . . . and lynchings followed by resistance to the civil rights movement. Some of this history went down right where we were talking—in the Historic Baptist Church of Camp Nelson. The small white clapboard church house has been breached and burned multiple times. Back in 1968—and most recently a couple of years ago when vandals broke into the building and desecrated the pulpit. Reverend Gates says most white folks in Jessamine County don’t like to talk about such things. . . . But Gates himself is done being quiet. GATES: You’re not going to tell me what I’m going to do. You may have done that 400 years ago. But baby, this is a new day. . . . I’m 60 now, and I’m getting like my mama. My mama said, “I don’t care. I’m gonna speak up.” And I’m going to speak up. Because if I don’t speak up, who’s going to speak up? Who’s going to speak up and tell that story? DAVID: The final leg of my tour takes me out of Jessamine County. I follow what’s known as the bourbon trail, past distilleries that make Kentucky’s signature drink. I drive past the most highly regarded horse farms in the nation to Frankfort, the state capitol. I’m here to see a truly disturbing object. DAVID: I’m at the Kentucky Historical Society with museum manager Jamie Bartek. And he’s just asked me to put on these green rubber gloves. Jamie, what are you about to hand me? JAMIE: David, what you’re looking at is a dessert spoon. But we often refer to it here as the lynching spoon. DAVID: Could you give me a physical description of it? JAMIE: Yeah, it’s about eight inches long. It’s silver. The handle itself has got some ornate engravings on it, some sort of beading on there. DAVID: There’s also an image on there, a pretty disturbing one. What’s being depicted here? JAMIE: If you look at this closely, you’re gonna see the writing on there. It says, “Nicholasville, Kentucky.” That’s Jessamine County. And it’s got a date on the inside of it as well by the lip. And it says “February 6, 1902.” And the image itself, if you just give it a glance, seems innocuous enough. Most of the bowl is actually taken up with a very intricate carving of the Jessamine County courthouse. And if you look a little bit to the right of the bowl, you can see a tree. There are leaves on there. You can actually see the bark that the engraver has made out. And then if you look even . . . more closely, what you’re going to see is a man being hanged from a limb. This represents an actual lynching that occurred of an African-American man in Jessamine County in front of the courthouse on that date. DAVID: What was his name? JAMIE: His name was Tom Brown DAVID: Why would someone do this? What’s the social function of a lynching spoon—or more broadly of a lynching souvenir? JAMIE: What's most disturbing about I find is . . . it’s classified as a dessert spoon itself, specifically as a dessert spoon. So is this this veneer of civility about it in a way that you know, this is this is how we handle things. And the fact that, you know, the prominent people from the community are often involved in these lynchings as well. . . . There was some skill, there was some time that went into went into making this which, again, shows that this is something that was given community approval. I mean, you're not going to make something . . . with this kind of skill to it and not think that you're going to you're going to sell it to somebody, somebody's going to buy it. There's going to be a demand for this. DAVID: Is the jeweler’s name on it? JAMIE: The jeweler’s name is on the back of it. Let’s see, I wrote it down here because I can’t quite read it it was so small. William W. Roberts . . . who was a jeweler in Nicholasville at the time. DAVID: Yeah, in fact I’ve located his shop. Pretty much across the street from the courthouse. JAMIE: So he saw this happen. Yeah. DAVID: Why do you think he put his name on it? JAMIE: This is something that he’s proud of. I mean . . . to create this kind of art, “Yeah, we’re claiming this, right? We’re claiming this.” . . . It’s community values that’s being expressed here. I put that in quotes: “community values.” But yeah, that’s what we’re talking about. DAVID: As Jamie hands the spoon to me, I think more about its maker. I had already encountered jeweler William Roberts in the pages of the Jessamine Journal. His downtown shop sold watches, fine china, and diamond rings. He also, apparently, hawked lynching spoons. As I gingerly hold this cold hard object, it’s the genteel form, as much as the horrible image, that disturbs me. It resembles the souvenir spoons that people in that era purchased at tourist attractions like Niagara Falls. This spoon does not lament a lynching. It’s a celebration. In fact, the lynching itself was a party. Accounts said that the whole city turned out, that all the women applauded at the end. Northern newspapers said that locals with guns fired hundreds of times into Tom Brown’s corpse. After the carnage . . . men, women, and children gawked at the mutilated body suspended in the air. Some took pictures. After the coroner cut him down, the crowd scrambled for keepsake pieces of the rope. Holding that lynching spoon—that’s when I feel the most betrayed by the statue in front of the courthouse. Yes, some defenders of the Lost Cause point to selected acts of decency . . . like the emancipation of Philip by the Young family. These are, indeed, historical facts. But there are a lot of other facts, selectively omitted from the Lost Cause our statue promotes. It does not commemorate the Black soldiers who enlisted at Camp Nelson to eradicate slavery. It does not remember the enslaved parents and grandparents of the strangled Black man who hung from a rope just a few feet away. Instead, the statue honors only the men who fought to keep them in bondage. I also feel betrayed by my own profession. Historians count 353 Black people who were lynched in Kentucky during Jim Crow. Three of the murders occurred in Jessamine County. But my own research so far actually documents fourteen lynchings. And that’s probably an undercount. Our Confederate statue doesn’t tell the full story. Nor have historians. DAVID: One of those historians was Bennett Young . . . the Confederate raider. Young published The History of Jessamine County, Kentucky in 1898. That was four years before Tom Brown’s lynching and two years after Young dedicated the Confederate statue. Like all historians, he selects his historical facts. Here’s one . . . having to do with the doors of the earliest pioneer cabins. They were made of riven boards, he writes, fastened together with wooden pins. There was a hole above the latch through which a leather string could pass and fasten to the latch. That “locked” the door. But every morning the string was untied. This practice, says Young, symbolized the “Kentucky proclamation of hospitality.” That proclamation went like this: “You will always find the latch-string on the outside.” But it’s important to remember that the string was really only unfastened for white people. Not for Black Jessamine Countians. For them, the string turned into a whip—and sometimes even into a lynching rope. Here’s an important measure of that inhospitality: The Black population here was 40 percent in 1860. Today it’s 4 percent. There are a number of factors, including economic ones, but the violent era of Jim Crow is a big reason Black people left when they could. This terrible lynching story ends with a redemptive twist. Remarkably, Black folks often responded with hospitality themselves. I saw so many examples of this in the Jessamine Journal. On May 1, 1896, a formerly enslaved veteran of the colored troops mustered at Camp Nelson issued an invitation to attend Memorial Day observances. And he invited quote “all regardless of race or color.” Two years later the colored Methodist church reserved seats for white people at a concert of Black spirituals. Sometimes hospitality extended even to forgiveness. There’s an account of an elderly Black man at Camp Nelson being approached by a white man on horseback. This man felt bad about his role in slavery and had come to apologize. MCBRIDE: What was the man? DAVID: This is historian Kim McBride conducting an oral interview with a 95-year-old woman named Margaret True who grew up at Camp Nelson. True still lived there at the time of this 1994 recording. And True’s daughter was there to help facilitate the interview. DAUGHTER: Uncle Marion Carpenter? TRUE: Uncle Marion Carpenter. He was 100 when he died. 100 years old. MCBRIDE: What did Marion Carpenter do for a living? TRUE: There was a distillery right there, you know. Most everybody worked at it. DAVID: She’s saying that Carpenter, like a lot of folks at Camp Nelson back then, worked at the local distillery. He was also revered in the community as a stone mason and folk doctor. MCBRIDE: Did he have scars? DAUGHTER: Wasn’t he a slave, mother? TRUE: Yes. His owner came to Camp Nelson later. He didn’t know him of course. He came on horseback to see him. He asked him if he knew where Marion Carpenter was. He said, “I’m Marion Carpenter.” He said, “I was wrong and ask you to forgive me. That’s what I’m here for.” He said, “Well, I can forgive you. But I can never forget you. Here are the scars.” Oh, wow. DAVID: It’s hard to hear her muffled voice, so let me repeat that last part. Carpenter, the formerly enslaved man, had said, “Well, I can forgive you. But I won’t ever forget you.” And then he showed his former owner scars from the whippings. That exchange took place in the 1890s. But the fraught work of forgiving and forgetting—and balancing safety and hospitality—continues. I saw it up close one cold February Sunday morning at Pastor Moses’s church. As we sang the opening hymn together, I noticed that I was the only white person there. Until I wasn’t. Suddenly another white guy—a disheveled man in ragged clothing—stumbled up the center aisle. The energy in the room instantly shifted—from joyful to very tense. It was hard to tell what was under his bulky jacket. “It’s not right. It’s not right,” he exclaimed. “It’s not right how they treat our children!” He was making no sense, and I tensed up too as the elders descended from the stage. They were completely coordinated . . . as if they did this all the time. In seconds they reached the man . . . and extended yet another act of hospitality. Gently putting their hands on his shoulder, they talked with him and even let him speak briefly to the congregation. Then they walked him to the back of the sanctuary. At the end of the service, an elder gave a report. The man was not dangerous. He had simply felt called by God to deliver a message. Perhaps, the elder continued, the man had been called by God. After all, we should be kind to our children. The church’s response was an inspiring act of dignity and compassion. But as we sang the closing hymn, “Jesus Is a Rock in a Weary Land,” I could detect in the congregation their own weariness—a long weariness. As ghosts of the violent, haunted past emerge in the fall of 2020, how will Jessamine County respond? In the next episode . . . a young white homeschooler makes her move. OUTRO: This is “Rebel on Main.” Thanks to story editor Stephen Smith, audio producer Barry Blair, the Kentucky Historical Society, the Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History at the University of Kentucky, and Asbury University and the Louisville Institute for their generous support. Be sure to subscribe to the podcast—and leave a rating and a review so others can find us. For pictures of the graveyard in Maren’s backyard, video of the outdoor drama, and photographs of the lynching spoon, head to rebelonmain.com. I’m David Swartz. See you next time.